After finishing my history degree and another year of courses split between the notion of becoming a Classical Archaeologist (I took some Greek and Latin) and a high school history teacher, I enrolled in a Master's program in Education. Most of the classes I took there were interesting and useful; some were fun. One, however, will always stand out: It was a course on curriculum.

"Curriculum" is one of those words that exist and get used without having a really good definition. What, exactly, is curriculum? Is it the list of topics that will be covered? The list of classes? The list of goals and objectives in those classes? Something broader: are 'extra-curricular' activities really 'outside' the curriculum, or do they count? What does a student learn being on a team, or in a band, or in a play? What about all the rules and regulations that students have to follow in school, which clearly teach things like values and habits - are those part of the curriculum? The discipline strategies that are used? The different pedagogical techniques - the same subject, but different lesson plans; is that a different 'curriculum'?

These are all good questions, but they're not the real issue. The real issue is deeper.

Our instructor for this course was a woman who had, if I recall, been an elementary school teacher and principal. She was a very nice woman, but very quickly we came to see her as, well, flaky.

The class met Wednesday afternoons, and because it met only once per week, it was supposed to be two and a half hours, from 4pm to 6:30. This was fall quarter at Ohio State (back when it did quarters; it's a semester school now, alas), and fall quarter began in late September and ran to early December. This would include the time change for Daylight Saving time, and so as the term progressed, the evenings grew shorter and eventually disappeared: the class would always end in darkness after sunset.

Our instructor was almost always slightly late to class; just a few minutes, occasionally more, but very rarely on time. More importantly - and happily, for us - she didn't keep us for the whole 150 minutes. Usually we got out early. That's especially nice as the evenings turned from fall gloaming sunsets to full winter blackness. Sometimes, instead of two-and-a-half hours, we were only there for an hour.

There were other bits of flakiness. I remember she lost my friend's term paper, and my friend had to print it out again and re-submit it. (Thank goodness my friend had done it on computer and had a copy; this was not a given in the early 1990s.) And the class seemed, to put it mildly, 'lightly prepared'. Sometimes it seemed like the instructor didn't even have her own notes with her.

In class (for the time we were there), we did odd things. We had readings and discussions, of course, but our instructor always seemed to be pretty casual about it, like the whole thing could be dismissed with a shrug. The collection of things we read and discussed seemed kind of like a hodge-podge. Along the way we also did in-class activities. One I remember - because I was the one put 'on-the-spot' - was an exercise where one person stood at the front of the class but facing away from it, and had to give another person instructions to create a paper airplane ("Hold the paper with the red stripe vertical and fold down the center..."), without seeing how the instructions were being performed. Once the instructions went off course, the creation got more absurd. (I think I did OK, actually - computer programming makes you think about what can go wrong with every instruction, and the thing that we had at the end of my stint looked more or less like a paper airplaine; it was a fun challenge.) There were other things like that, which were very weird for a graduate-level course. A few of us thought (in private, of course), that it seemed more like our instructor wanted to teach elementary school than graduate school.

And then, she did what we all thought was the epitome of flakiness, something so odd that we couldn't believe it: The final exam, she said, would be a group, oral exam.

Huh?

Among other issues (like that it would apparently require almost no grading from the instructor - again, flaky), it means your grade depends on the group, which is, frankly, scary. But, more importantly, how does a 'group, oral exam' even work? It seemed like it would just be another class discussion, only with consequences that were mostly unpredictable. How do you prepare? What's actually going to happen when you get there? In other words: WTF?

Curriculum is one of those words that doesn't have a good definition. But beyond the idea of a list of topics or subjects or goals to be taught, the deeper issue is: How does a set of activities - things a person does - result in learning - things a person knows? How does that happen? What's the mechanism?

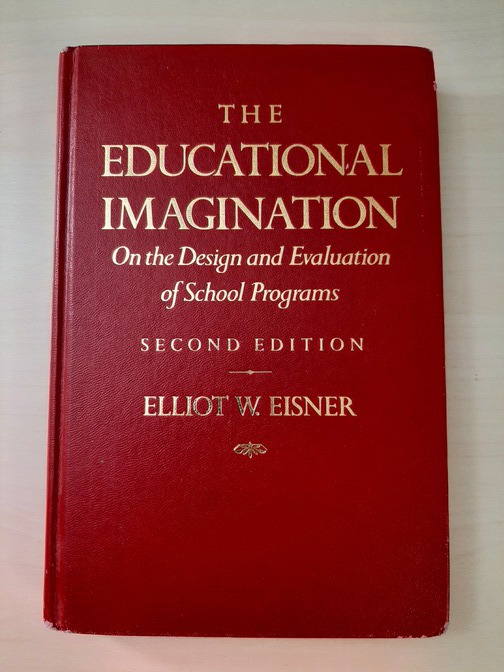

Our main book for the class was entitled, "The Educational Imagination." The title carries the point: There are lots and lots of ways to teach, as well as to learn, and although in some ways it's fully mysterious, in other ways that mystery gives you space, and it allows you to do your teaching in a lot of different ways.

We arrived for our 'group, oral' final exam, at the end of a flaky class with a flaky instructor, and just shrugged our shoulders as we got ready for whatever would happen next.

Our instructor had a set of index cards, and after we settled in to our seats, she began to ask questions from them. And this is what I remember most about the class: Because as the questions kept going, one by one, we all realized that the class hadn't been a hodgepodge: it was a puzzle. The exam, it turned out, was the key. Every question she asked, and that we, as a class, figured out together, would put another piece of the puzzle into place. I remember feeling amazed when I realized how the pieces clicked together, but even more, I distinctly remember almost being shocked when after a few rounds of this, I realized that if she just asked this question and put these pieces together then I knew what the next question is going to be. (And it was.) It wasn't just me; after the class, one of my friends just said, "Wow."

It was a magic trick. The whole 'flaky' semester came together in one, gorgeous picture.

Curriculum is like music: It can be rigorous and structured, it can be sacred choral music, or it can be country, or jazz, or pop, or rock, or bouzouki. But we, as new teachers, would never have to look at it as something with limits again. We could do the weird activities, we could let pieces sit around and find new ways to guide the students to putting them together. It wasn't random, and it wasn't just chance: it had to be designed. We had to wrestle with that question of how kids - and not just any kids, but our kids, in our classes - would move from doing things to knowing things. But that curriculum could be designed in a myriad of ways, finding different routes to light students along their learning journeys. This 'flaky' course was not just a magic trick; it was a gift.

It was the best class I ever took.