I'm baffled by the fascination with generative AI. I will admit, it's very cool. And it offers some fodder for thinking about the level of skill and talent that it takes to do certain things- like write, for example. Writing is, to me, very personal; it's my voice and no one else's. But a chatbot can create the same sentence, the same sequence of tokens, and thus the same 'voice' as mine. (Side note: Perhaps somewhat paradoxically, these things don't use words; they use pieces of words called 'tokens'. It's easier for the output to replicate our language if the processing doesn't actually use the same elements as we do.) What is the unique value of my voice is the same thing can also be generated by a computer?

The answer is, simply, that I'm a person. I matter. Chatbots don't.

That's the perspective from the writer's view, but I'm really more interested in the reader's view. Because I'm confused about why people would want to interact with these chatbots at all.

Mind you, I'm not seriously advocating interacting with people instead- not necessarily. I'm quite a loner. I live by myself and can go days without talking to another person. I'm smack in the middle of the target demographic for 'AI companions', and probably a good type specimen for our current epidemic of loneliness. I know the names of perhaps four people that I know for sure live within ten miles of me; I haven't spoken to any of them in a decade or more.

The problem is, I like that. I know full well how to connect with a community; I could easily leverage my few existing connections, or make more of them. And, yes, there are a few people that I wish I'd seen more of in the last several months. But I'm very, very happy to connect with a few people remotely (one of my good friends is in France), and spend the rest of the time on my own. I read a lot. It's awesome.

If you happen to be a person who likes company, has friends, and spends evenings in 'third places' where you get social interaction, great. Good for you.

But that's not my point here. I'm not advocating that people abandon chatbots to interact with real people. The second part of that is irrelevant: what they do if they abandon chatbots is their business.

What I'm concerned about is the nature of the interaction when people do interact with chatbots.

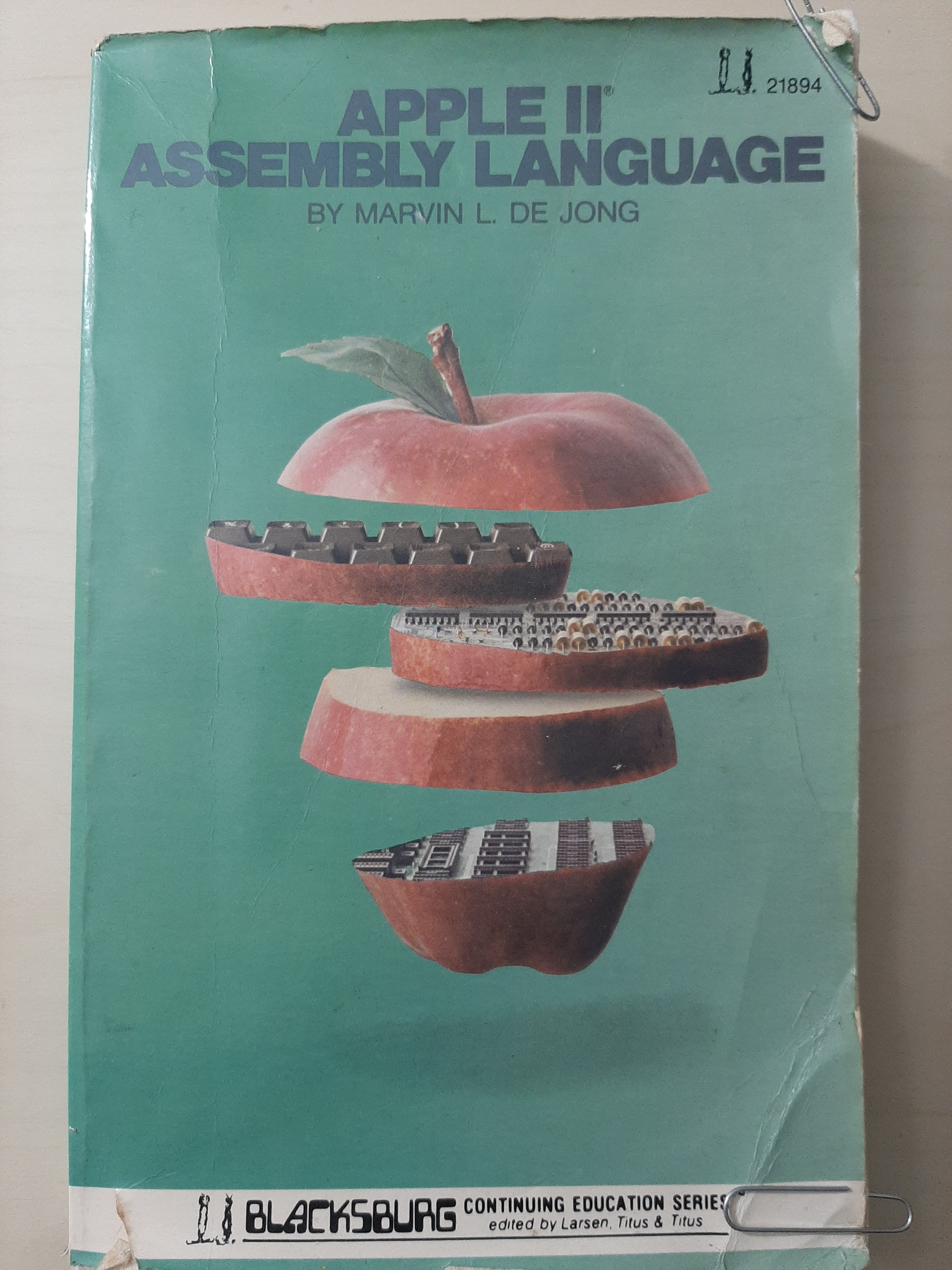

I am a Gen-Xer, and I'm very proud of it, and also very happy that the curve of my life has spanned the things that it did. I was still in the womb when Armstrong stepped on the moon, but the level of technology we had to guide those rockets was infantile compared to today, and as I grew up, so did it. I had the Atari 2600 and the Commodore Vic-20 (yes, before the Commodore 64). The Apple IIe I eventually got was fantastic.

But that level of technology was very different than today's in one crucial way: We didn't just get it to use it; we got it, in part, so that we could learn to take it apart and put it back together. (Sometimes literally: my roommate in college took the motherboard out of his IIe and mounted it on the wall, still running and usable.) I owned not only the Vic-20 and the Apple IIe, but the technical diagrams for both of them- the map of the circuit board, the specifications for the chip. I wrote my own games. Did I use BASIC? Yes. I also wrote in assembly.

My point is not that I was an awesome programmer. My point is that the computer worked for me.

If the computer didn't do what I wanted, I opened it up (metaphorically or literally) and modified it. I controlled the input, and I controlled the output.

This means that if it said, "Hi John, how are you today?" it was not because it wanted to know how my day was; it did that - and anything else - for one reason and one reason only: because I told it to.

Naming the computer (remember Apple's Lisa? Microsoft Bob?) was cute, but silly; there was no Lisa and no Bob. There was no ELIZA, either. I don't deny that interacting with something like ELIZA could be helpful. But it was always more interesting for me to ask how ELIZA was written than what ELIZA would 'say' next.

Meanwhile, though, as our society adapted to technology, a strange thing happened to our interactions. We began to live in a Turing test.

Turing's test is well-known, and it's usually stated that if you can't tell the difference between interacting with a computer and interacting with a person, then the computer is 'intelligent'. But that's not really all of it. Turing's test was written for a specific period: it presumed that you would be interacting with this computer (or human) via a teletype. All you would get is text.

This privileges a specific kind of intelligence: the ability to manipulate symbols. And that's fine- but it's not human. Dance is intelligent; feeling the sting of a bee is intelligent; remembering the crust of your grandmother's pumpkin pie is intelligent. Turing didn't care about that. If the computer could fake the symbols to say that it remembered it, that was the same. (We also devalued these other intelligences: dancing and making pies are not 'smart', and it's not a coincidence that they are also not 'masculine'.)

Over time, we began to interact with other humans via teletype: chat rooms initially, then email, and then, much later, text messages. Our interactions with real people have become blurred into interactions with devices.

[I didn't use chat rooms, and I'm a lousy texter. Again, I'm a loner. But I am Gen-X, so I'm awesome at email.]

In the world we've created, the way we interact with people depends heavily on getting them to produce the right symbols on our screens. Consequently, we now acquiesce to Turing: if something (a person or a chatbot) puts the right symbols on our screens, we are content to consider it intelligent. In fact, we've created something of a gray area, where it's sometimes hard to know if the responses are from a bot or a computer. If you text someone, and their response is just selected from the auto-generated replies, which is it? This was always going to be the outcome of trying to make systems 'intelligent' by trying to make them like ourselves. It's a Frankenstein world. It's no coincidence that many people today mistake a never-ending onslaught of social media posts for personal traits like intelligence and indomitability: generating text, any text, is 'intelligent' on its own, never mind the content.

But this is where I'm not on board at all with this approach. If a computer is putting symbols on my screen, I assume that it's working for me. Well, almost- we'll get to that. But I don't believe the computer wants to know how my day is going, wants to listen to my views on Bach or baseball, or wants to know anything about me at all. It's a computer. I can take it apart and make it do other things.

The only reason you would want it to talk back is if you wanted to cede some control- to be surprised, to pretend that it's pushing you or pulling you in specific directions.

And, here I have to admit that there is a catch- the 'almost' from above. It may very well be pushing you or pulling you in specific directions, but if it is, it's because it's not working for you. And if it's not working for you, it's working for someone else.

This fact that it's working for someone else is also a thing that we have built into our system, and also something I have no interest in. We are now very accustomed to letting algorithms determine our content intake: we 'trust' the algorithm to know what we like. An app 'works better' if it feeds us content that is 'relevant'. Ads are more appreciated if they are 'targeted'.

My own experience with this is fully negative. I make sure to give as little information about myself as I can to advertisers, and have diligently trained myself to look first at the signature of a social media post to determine who posted it, and then - and this part is very important - DO NOT READ IT if it's not an actual friend. I suspect that when I'm on a website a substantial portion of my brain is given over avoiding the distractions of the ads. (This is why there are none on my website, and won't be, ever.) My experience with apps like Instagram Reels and TikTok is basically that they establish that I'm male, and then start feeding content by guessing I will like videos of hot girls doing anime cosplay. Later they eventually they devolve into an endless stream of cat videos. I'm happy about that, I guess; some days I need a cat video. But it's not much more than that for me.

And it is definitely NOT a news source. Because, just like I am better at writing than a bot, I'm also better at research than a bot. I worked hard to become better at research. As a Gen-Xer, I actually used library card catalogs (the real ones on index cards), and then grew up with computer index systems (ARCHIE, VERONICA, ERIC- good times, before Larry and Sergei developed their indexing algorithm, and well before they converted it to harvest data and make profit).

This is a role reversal: In my view, the computer works for me, and I am 100% in control. There is nothing in the output of a chatbot that I view as in the slightest bit interesting, never mind 'intelligent'. But in the way that many people seem to interact with chatbots, they cede the authority to the bot. They ask the bot questions because they believe the answers; they respond to the bot because it guides them.

It's a pocket calculator. Nothing more. Can it help you add big numbers? Sure. Is it going to solve climate change? No. It's just vastly easier to say it will solve climate change, and sell it as a way to solve climate change, than to, say, actually train an army of people to study the climate and the array of responses, and then to fully educate a citizenry, so that you can publicize the research in a digestible way that leads to concrete action. Doing that would be hard, and difficult to monetize. So Silicon Valley proposes that they can do it better, if we just give them the money, and then cede the authority to them, so that we listen to what they and their computers say.

Which brings me back to the main point of the essay. When I interact with a computer, I'm using it. Always. I own it; I force it to do what I want; I can take it apart and make it into a completely new thing. It's like a giant floor where I have an infinite supply of dominoes: I can set them up any way I want, and I can look at the output for anything I need, but it only matters if I say it matters, and it only happens if I say it happens. There is nothing more.

And this is the critical point, because this is exactly the opposite of my interactions with people. The fact that I'm a loner is only a preference; I do, in fact, like people, and more than just liking them, I care about them. And because I care, I can see the things that are missing from my interactions with computers that must, as a guiding principle, be in my interactions with people: Kindness means thinking of the other person; caring means thinking of the other person first. Decency means making sure that the interaction helps them - makes their day better, makes their lives better. Compassion means finding the right words or actions to lift them up. It's a crappy world sometimes - the barista gets your order wrong, the person at the DMV has to follow rules that make no sense, and the people in front of you in line at the store are making a scene. It takes thought and care and commitment to find the way to make things better.

It takes grace.

I do not need to grant grace to a computer; that's irrelevant. And I can't really receive grace from a computer; a computer might replicate that, but can't really grant it.

So, the real question is, how much of our interactions need to be guided by grace?

I think the way we collectively answer that question will determine a lot about how we shape our future- with or without machines.